The Dollar or the Man?

| Economic Disparities Arbitration in a Strike |

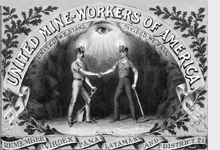

In one of his more powerful cartoons, Davenport displays the fat oligarch pummeling the hapless worker, as his weeping family stands by. Laborers during this time were increasingly becoming more organized, lubricating the growth of labor unions, such as the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). The economics of coal revolved around two factors: most of the cost of production was wages for miners, and if the supply fell, the price would shoot up. In an age before the use of oil and electricity, there were no good substitutes. Profits were low in 1902 because of an over supply; therefore the owners welcomed a moderately long strike. They had huge stockpiles which increased daily in value. It was illegal for the owners to conspire to shut down production, but not so if the miners went on strike. The owners welcomed the strike, but they adamantly refused to recognize the union, because they feared the union would control the coal industry by manipulating strikes. In one of his more powerful cartoons, Davenport displays the fat oligarch pummeling the hapless worker, as his weeping family stands by. Laborers during this time were increasingly becoming more organized, lubricating the growth of labor unions, such as the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). The economics of coal revolved around two factors: most of the cost of production was wages for miners, and if the supply fell, the price would shoot up. In an age before the use of oil and electricity, there were no good substitutes. Profits were low in 1902 because of an over supply; therefore the owners welcomed a moderately long strike. They had huge stockpiles which increased daily in value. It was illegal for the owners to conspire to shut down production, but not so if the miners went on strike. The owners welcomed the strike, but they adamantly refused to recognize the union, because they feared the union would control the coal industry by manipulating strikes.The UMWA had won a sweeping victory in the 1897 strike by the soft-coal (bituminous) miners in the Midwest, winning significant wage increases. It grew from 10,000 to 115,000 members. A number of small strikes took place in the anthracite district from 1899 to 1901, by which the labor union gained experience and unionized more workers. The 1899 strike in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania, demonstrated that the unions could win a strike directed against a subsidiary of one of the large railroads. It hoped to make similar gains in 1900, but found the operators, who had established an oligopoly through concentration of ownership after drastic fluctuations in the market for anthracite, to be far more determined opponents than it had anticipated. The owners refused to meet or to arbitrate with the union; the union struck on September 17, 1900, with results that surprised even the union, as miners of all different nationalities and ethnicities walked out in support of the union. Republican Party Senator Mark Hanna from Ohio, himself an owner of bituminous coal mines (not involved in the strike), sought to resolve the strike as it occurred less than two months before the presidential election. He worked through the National Civic Federation which brought labor and capital representatives together. Relying on J. P. Morgan to convey his message to the industry that a strike would hurt the reelection of Republican William McKinley, Hanna convinced the owners to concede a wage increase and grievance procedure to the strikers. The industry refused, on the other hand, to formally recognize the UMWA as the representative of the workers. The union declared victory and dropped its demand for union recognition. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. |